Gordon Menzies

Associate Professor in Economics at the University of Technology Sydney

Disciplinary Brief

An earlier version of this Brief was presented as the opening address of an Oxford Faculty Workshop on “The Sovereignty of Love” hosted by GFI in partnership with the Lanier Theological Library, Yarnton Manor, 6 June 2025.

I am attracted to the summary sayings in scripture. These passages distil vast theological territory into memorable phrases. The Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1-17) reduce the complexities of covenant life to ‘ten words’ (Deut 10:4). Paul's "trustworthy sayings" crystallise essential gospel truths into reliable formulations (1 Timothy 1:15, 3:1, 4:9; 2 Timothy 2:11; Titus 3:8). The Shema declares Israel's foundational faith: "Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one" (Deuteronomy 6:4). The Lord’s Prayer (Matt 6:9-13) covers so much of our relational life with the Father.

And, pertaining to the topic of O’Donovan’s Theology Brief, Jesus identifies the Great Commandment as the peg that holds up all moral and religious obligations (Matthew 22:37-40, Mark 12:28-31, Luke 10:27).

'Jesus replied: Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.' This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.’ (Matthew 22:37-40 NIV)

Perhaps because I am a mathematical modeller, I cannot help seeing in these summaries a kind of ‘scriptural model’. A model is a framework that helps us to make sense of something much larger and more complex. A good model is simple – evoking an ‘aha’ as things fall into place. It is a seed with plenty of room to grow, and yet everything essential is packed into that small parcel. In contrast, a simplistic model must be unlearned as one goes: as one’s understanding develops, these original thoughts must be discarded.

What is so helpful about scriptural models is hat they are themselves part of divine discourse and not abstractions from it. To my mind, this guarantees that they are simple rather than simplistic.

If we take seriously the idea that these scriptural summaries function as reliable models for understanding complex realities, then we must ask: what happens when we apply this same modelling approach to academic scholarship itself? How might Jesus' Great Commandment serve not just as moral guidance, but as an explanatory framework for academic work?

What I admire about O’Donovan’s work is that the echo of the scriptures is resonant in it. I recently heard a famous philosopher discuss these same commands. It was a deep discussion of theories of action and nuances of love, and I am not qualified to give an overall assessment of it. But one thing that did stand out to me was that whenever the discussion turned to things related to the Bible, there was a kind of discomfort in the discourse, as though two kinds of descriptions – philosophical and theological – were at war with one another. O’Donovan never gives that impression. His loyalty to scripture and his belief in its fruitfulness shines.

This theological brief on the Sovereignty of Love provides exactly the kind of analysis the greatest commandment deserves. O’Donovan’s entire piece examines the significance of Jesus’ identification of love as the summary of all moral and religious obligations, and I find his insights both illuminating and challenging for how we might think about academic integration. Colossians 3:14 has long been a significant verse for me, and it rebuts the claim that love is just one virtue among many. It reads: ‘And over all these virtues put on love, which binds them all together in perfect unity. (NIV)’

O’Donovan defines love as "affective and directive attention to the good of persons"—combining genuine feeling with purposeful action that shapes human existence. This definition emerges from an exegesis of Jesus' teaching and reveals several crucial dimensions that I had not fully appreciated before reading his work.

O’Donovan shows that love is not a static principle but an orderly sequence of moments—contemplation and action, sacrifice and enjoyment, decision and habit. Love develops through time, creating what he calls "a narrative arc that gives shape to a life lived as a whole." This temporal understanding prevents us from reducing love to any single moment or expression and seems to get the balance right between analysing relationships in the abstract versus seeing them as biographical and particular.

As O’Donovan explains, "on love 'the law and the prophets hang,'" meaning they derive their intelligibility from it. Love provides insight into Scripture's diverse forms and functions as a form of practical reasoning that resolves seemingly irreconcilable moral demands.

A key point here is that ‘the law’ includes much of what we moderns would most naturally classify as ‘justice’. This leads to an intriguing observation that O’Donovan makes, but does not develop fully.

For Aristotle and Plato, justice served as the supreme, organising principle that coordinated all other virtues - the same role that love plays in Christian ethics.

"For both these thinkers justice was differentiated by a kind of universality, which put it in a position analogous to that of love in Jesus's teaching." This observation was very interesting to me because I recently read Plato’s Republic for the first time, and I was struck by how Plato gives no simple answer to the question, ‘what is justice?’. Instead, he seems to regard it to be a property of a well-ordered society and person.

O’Donovan has an integration between love and justice in his mind when he says that love seeks justice as its goal in public and social order, but love can go further, providing something that public justice cannot: the personal attention to particular goods and particular people that makes moral action both meaningful and sustainable.

O’Donovan demonstrates that love is fundamentally a way of knowing created goods. His insight that "to love, we must learn to recognise personal singularity", while also grasping things "as" what they truly are, has profound implications. When we love something appropriately according to its nature, we come to know it more fully.

Relatedly, O’Donovan notes that "truth is the criterion of both love and knowledge"—they are not opposed but deeply interconnected. Since he says that the proper target of love is persons, we may extrapolate the following axiom: ‘When we love people appropriately according to their nature, we come to know them more fully.’ I will return to the profound implications of this axiom below.

O’Donovan's analysis reveals that the goal of connecting scholarship to the love of persons cannot be achieved in isolation.

O’Donovan recognises that some academics work on specialised and impersonal subjects – such as the mathematicians who worked out the non-Euclidian geometry Einstein worked with, before it had any apparent use. He helpfully guides those who work on specialised knowledge to think of their work as a vocation: to understand the ordering of reality, and to provide education to others. Each of these could lift the spirits of a Christian working in specialised areas, far from persons, and far from an obvious expression of love.

Another dimension that a scientist shared in response to O’Donovan’s piece is that one has a wholly different appreciation of an exhibition of art if one knows the artist. O’Donovan gives the example of Bach’s wife in this regard, and (as my colleague put it) a scientist studying the most impersonal of physical objects can worship and love God at the same time, as the proverbial artist responsible for the artwork.

Different disciplines offer different gifts within Christ's body of scholarly work. A mathematician's love for elegant proofs, a historian's love for understanding human agency, a psychologist's love for behavioural complexity—all contribute to our collective understanding of God's creation. No single discipline captures the full scope of reality, but each offers essential insights when properly ordered towards love.

I now want to outline four areas of O’Donovan’s piece that excited my imagination and, since we are talking about love, warmed my heart.

Whenever I have taught ethics within my discipline of economics, the following question has arisen: does the practice of a virtuous person consist of no more than following good rules and seeking good consequences? If a virtuous person is simply one who meets both of these obligations, then one wonders if placing virtue ethics alongside deontology and consequentialism as the three frameworks for ethics is some kind of category mistake.

O’Donovan’s whole-of-life narrative arc for a loving person seems to open up a notion of virtue ethics that is conceptually distinct from deontology and consequentialism.

Or, to put it another way, his discussion highlights a conceptual problem with the way virtue ethics is conceived. It is supposed to focus on the agent, and yet when it is discussed in academic circles one must imagine an abstract, ahistorical agent. O’Donovan’s discussion of love emphasises knowledge of the particulars of people and created goods. In contrast, any ahistorical approach ignores the predominant way virtue ethics has been used by most people throughout most of history: the cultivation of virtue by the imitation of specific exemplars. Once the ahistorical method for virtue ethics is abandoned for a biographical one, Jesus Christ is a natural place for a Christian ethicist to turn.

Jesus is one-of-a-kind, so his identity as the Son of God and his unique mission do rule out following him in, say, the provision of salvation, notwithstanding the general call to imitate him (1 John 2:6, 1 Cor 11:1). Christians are called to imitate Christ with respect to suffering justly (1 Pet 2:21), humble service (John 13:15), sharing his yoke (Matt 11:29) and displaying sacrificial love (John 13:24-25, Eph 5:2, Phil 2:5-8).

The ideal set of exemplars will include more than Jesus, however. Many important exemplars relate to narratives of repentance and humility after failure (c.f. Ps 51 for adultery and murder). Finally, believers have always needed what scripture cannot provide: contemporary models of Christians living in the same cultural milieu.

Such a virtue ethic is, of course, already embedded in the practice of many Christian traditions, with longstanding ones more inclined to explicitly recognize past exemplars of faith. An academic agenda where Christian ethicists show more explicit deference to Jesus and Christian exemplars would be in keeping with O’Donovan’s practice of letting theology dictate the categories for academic enquiry, and would help bring Sunday and Monday together for these scholars.

O’Donovan discusses the Hellenistic tendency to use justice as an integrative device in the ancient world, similar to the way Jesus calls Christians to use love. That struck me as a very interesting observation, and I cannot help wondering if what was true of ancient Greece is true today.

When I worked at the central bank in Australia, I could have had a discussion with my colleagues that began with the words ‘I think inflation and unemployment are unjust’. O’Donovan’s article prompts me to imagine an intellectual world where the statement ‘inflation and unemployment are unloving’ would be taken similarly seriously.

We are certainly not in such a world.

John Rawls, perhaps the most influential political philosopher of the late 20th century, begins his landmark work A Theory of Justice (1971) by declaring that "Justice is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is of systems of thought". The implication is that justice does some of love’s integrative work, as the ancient Greek philosophers claimed. But what would it look like if we Christians could think about love in such a way as to declare “Love is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is of systems of thought”.

To think this way requires invoking love in interactions which appear impersonal, and which might otherwise be cast in terms of justice. For example, the far-flung anonymous reaches of the market raise the question of 'distance' in love as it relates to economics. Distance appears in all sorts of contexts and makes the particular actions required of effective love harder to discover. Similarly, there is distance between the agent and 'the person loved' in the way that scientists contribute to the love of persons. When a scientist makes a discovery, there may be many intermediate agents between the discoverer and any final technological user. Medical discoverers are the fortunate position of almost always contributing to human flourishing, whereas other research, such as the splitting of the atom, may contribute to more problematic applications. Nevertheless, once distance is acknowledged, there are good ways of running markets or organising the uses of academic discoveries which we might be tempted to call ‘justice’. I would prefer to call them ‘love at a distance’.

O’Donovan himself has not made the mistake of using justice where love should be used – indeed the whole purpose of his Theology Brief is precisely to reclaim the sovereignty of love over all usurpers, which I assume includes justice. But perhaps our contemporaries, or indeed we ourselves, have made the mistake of following Rawls by dethroning love as the integrator and replacing it with justice. This is not to write off Rawls, who was seeking to rescue us from thinking only in terms of power; but one can still ask if we are committing the error of the ancient Greeks.

Perhaps we are making this error, and perhaps this is why it has taken so long to have the conversation we are having today. It may also be one reason why we might feel more embarrassed to quote Jesus in an academic seminar than we would to quote Plato or Aristotle.

O’Donovan writes that in order to love we must grasp things as they truly are and, when we love something appropriately according to its nature, we come to know it more fully. As he so beautifully puts it: "truth is the criterion of both love and knowledge". So, I take it that knowledge is both a requirement and a result of love. Secondly, O’Donovan says that the ultimate telos of love is persons.

Putting the two together, we may say that to love properly – that is, to love persons – we must understand persons as they truly are, and that the act of loving them will teach us what those persons truly are.

An important implication of this is that a failure to love distorts not just our character but our apprehension of the world, which theologians call a noetic effect of sin.

There is in fact a correspondence between O’Donovan’s account of the Greatest Command and Emil Brunner’s (1946) account of the noetic effects of sin. What is common to both is the centrality of persons. To return to my introductory theme, namely modelling, I think O’Donovan’s implicit account of persons gives us a high-level model for understanding Brunner’s noetic effects of sin.

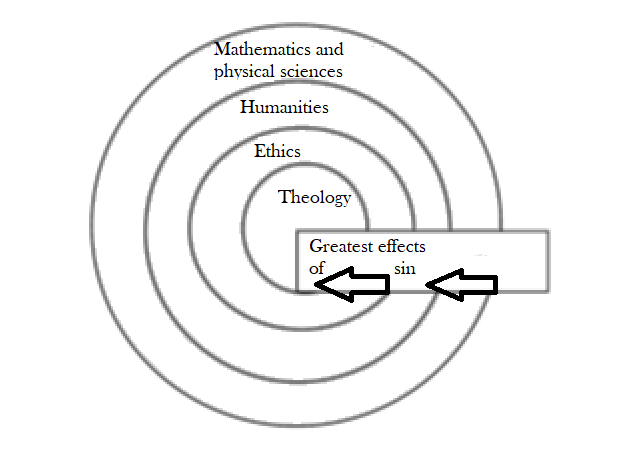

Brunner argued that sin's distorting effects on human knowledge operate along a spectrum. Mathematical and natural scientific knowledge sits far from what he called the Personkern—the personal centre of human existence—because they deal with impersonal phenomena. Economics occupies a middle position, dealing with human behaviour, but often through aggregated, statistical patterns that obscure individual personality. Disciplines like History, Ethics, Theology, Law and Psychology, however, sit very close to the Personkern because they fundamentally concern human agency, decisions, and the meaning of personal and collective actions. [ 1 ]

Here is the model:

An economist may fail to acknowledge a spiritual component to people and treat them as rats in a maze responding to stimuli. A psychologist may have a conception of human autonomy that exacerbates selfishness and godlessness. A sociologist may fail to see individuals at all, seeing only a generic group-person, a product of social forces. All these errors, and others, lead to failures in love, which further cloud our understanding.

Paul's image of the body of Christ (1 Cor 12) is germane for any academic. Just as the body requires different members with diverse functions, Christian scholarship requires a community of scholars with different expertise working together to serve love's purposes.

I have learnt from O’Donovan’s vision that fellowship with other academics has a value that goes beyond helping us to publish, or explain and display our faith to our colleagues, or to manage our time. It should be part of our vision to celebrate how academic life leads to loving outcomes.

As an academic economist, I like to think of myself as part of a community which occasionally makes a big impact, and I am encouraged by stories of the really big impacts economics has made in history, such as how economic policy deals with crises far more effectively now than it did in the past. But others might like to hear more about how small acts can have small but real effects. Universities are already seeing the need to do this. The kind of story about love’s impact that a particular person finds encouraging may vary, but O’Donovan’s overall vision of contributing to a wide community is surely correct. And his emphasis on teaching reminds me to include both my current and past students within my conception of my own academic community.

This response to Oliver O’Donovan’s Sovereignty of Love does not cover every avenue for exploration, but I hope it prompts a number of conversations, some of which will be carried out by those in disciplines far from my own. For any conceptual mistakes buried within my observations, I apologise in advance. Hopefully, these can be corrected by other Christians in the academic community.

We need fellowship not only to correct each other, but because integration is not an easy journey. If Brunner is right, social scientists and others who work close to the Personkern face the difficulty that persons are both what we should love most (as Jesus taught) and what we academics distort the most.

And if the Hellenistic tendency to use justice as a master-virtue has continued, we may all be off course by speaking the language of justice when (sometimes) the language of love is better. There is, in fact, a strange disconnect between the regular and wide-ranging appearance of love in ordinary discourse (and the teaching of the scriptures) and its notable absence on the lips of our colleagues. In ordinary life, it preserves considerable semantic range that integrates justice, such as when we speak of ‘tough love’. But in the academy, there is a real question about whether justice has overtaken love as the integrative principle, as it did in Ancient Greece.

Naturally, one is at liberty to disagree with O’Donovan’s perspective on the Great Commandment, but a Christian person is not at liberty to disagree with Jesus himself. However one reads Jesus, he said the love command is the ‘greatest’. As Christian academics, we cannot merely echo Jesus' declaration in our personal lives while ignoring it – and indeed him – in our scholarly method.

There was a time in the history of the West when becoming an academic meant joining a spiritual order. That had its downsides, and I for one greatly appreciate the contributions of people with very different worldviews to myself. Nevertheless, if we are to move beyond the reductionist impasse that has plagued the Humanities, we may need to recover something of that earlier integration—not the institutional constraints, but the recognition that love is both method and meaning. Organisations like GFI and the Lanier Theological Library are already demonstrating what this alternative looks like, building intellectual communities that refuse to compartmentalise Christian faith and rigorous inquiry. I want to thank O’Donovan for his very stimulating and spiritually wise reflections in The Sovereignty of Love, which shows us that returning love to its rightful place in academic discourse is not a retreat from good scholarship, but an advancement towards it.

Brunner, Emil. Revelation and Reason: The Christian Doctrine of Faith and Knowledge. Translated by Olive Wyon. Wake Forest, NC: Chanticleer, 1946.

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971.

[ 1 ] To quote Brunner “The nearer anything lies to that centre of existence [Personkern] in which we are concerned with its totality – that is our relation to God, and our personal existence – the greater the disruption of rational knowledge through sin. The further that something lies from this centre, the less the impact of this disrupting factor, with a corresponding reduction in the difference between the knowledge of the believer and the unbeliever.” (1946, 383)

Download